A stainless steel Old Army, ready to go, in percussion configuration. A powder flask, some conical and/or round bullets, and percussion caps are all that’s needed.

The Centennial of the American Civil War in the early 1960’s created a demand for replicas of weapons of that period. A number of importers entered into cooperative ventures with firms in Europe to produce revolvers based on patterns of the period. One of the best known revolvers of the Civil War was the Remington Model 1858, a robust .44 caliber percussion weapon. Replicas of the Model 1858 are enormously popular among black powder modern shooters, especially in the “Cowboy Action Shooting” (CAS) game. Ruger was fairly late getting into this market, but when they did enter it they did so with a carefully-thought-out revolver that was not just second to none: it was head and shoulders above the rest of the field.

In 1972, Ruger introduced what they called the “Old Army” revolver. The reason for this designation is inexplicable: the Old Army is neither old, nor was it ever used by any army, anywhere or at any time. But that is of no importance: what’s important is that from the beginning it was a success, owing largely to its advanced materials and engineering design.

The stylistic lineage of the Old Army is apparent when it is laid alongside a replica Model 1858 Remington. Internally the two guns are very different! The Model 1858 was one of the best handguns of the American Civil War; many of them were carried by pioneers in the post-war western expansion, and were fitted with conversion cylinders essentially identical to those available today.

In style the Old Army is—very loosely and mainly stylistically—based on the Remington 1858. Like the Model 1858, it’s a solid frame percussion gun with an integrated ramming lever under the barrel, and of course it’s a single action. But other than these superficial resemblances the Model 1858 and the Old Army are as different as chalk and cheese. The Old Army is really based on another of Ruger’s extremely successful single-actions, the “Old Model” Blackhawk, introduced in 1955 (below).

The Blackhawk was an immensely strong revolver designed for powerful fixed ammunition (.357 Magnum, .30 Carbine, and .45 Long Colt, among others). As a Blackhawk derivative, the Old Army—which was intended from the start to use loose powder and ball, not fixed ammunition—is far stronger than any other percussion revolver. There are many similarities in lockwork and construction between the Old Army and the Old Model Blackhawk, to the point that some of the parts will even interchange between them. According to the Old Army Owner’s Manual:

The Blackhawk was an immensely strong revolver designed for powerful fixed ammunition (.357 Magnum, .30 Carbine, and .45 Long Colt, among others). As a Blackhawk derivative, the Old Army—which was intended from the start to use loose powder and ball, not fixed ammunition—is far stronger than any other percussion revolver. There are many similarities in lockwork and construction between the Old Army and the Old Model Blackhawk, to the point that some of the parts will even interchange between them. According to the Old Army Owner’s Manual:

The RUGER® OLD ARMY® percussion revolver is an original Ruger design and is manufactured to our regular standards of strength and reliability, entirely in modern Ruger factories in the U.S.A. The best quality steels and coil springs are used throughout, the same as in our centerfire cartridge revolvers. Stainless steel nipples are standard and grip panels are genuine American Walnut. The mechanism of the “Old Army” has been carefully designed to retain traditional handling and firing characteristics of the old-time “cap and ball” revolvers while at the same time incorporating improvements (U.S. and Foreign Patents) which mark the first significant advance in percussion revolver construction in more than a century.

All this is exactly correct. The internal lockwork of an Old Army is vastly different from that of the guns of the 1860’s, and is basically that of the Old Model Blackhawk. Modern engineering design principles were applied to it: its stainless steel coil springs can’t break or be overstressed, as leaf springs can be. The receiver and grip frame are investment cast. Investment casting produces items of intricate shape that couldn’t be made using conventional machining methods at all: and not only are investment-cast parts immensely strong, they emerge from the initial stages in nearly finished condition, requiring only minimal post-casting modifications, if any. Ruger has experience with the method going back decades: they have produced many products besides guns using it.

The percussion nipples of the Old Army cylinder are another example of “engineer-think.” Nipples on original guns (and almost all other replicas) are screwed in and out with a somewhat fragile wrench having a single large slot. The Old Army’s nipples use a hex head design of standard SAE size instead. This may not sound like a big deal, but anyone who’s had to contend with a rusted-in-place conventional nipple and bent or stripped out a traditional wrench in the process will agree that force is far better distributed and torque enhanced by the hex-head design.

The percussion nipples of the Old Army cylinder are another example of “engineer-think.” Nipples on original guns (and almost all other replicas) are screwed in and out with a somewhat fragile wrench having a single large slot. The Old Army’s nipples use a hex head design of standard SAE size instead. This may not sound like a big deal, but anyone who’s had to contend with a rusted-in-place conventional nipple and bent or stripped out a traditional wrench in the process will agree that force is far better distributed and torque enhanced by the hex-head design.

Some thing you aren't normally supposed to do with percussion guns is to dry fire them: this will cause the nipples to “mushroom” and produce misfires. But Ruger’s engineers provided adequate clearance between the hammer face and the nipple to permit safe dry firing. The owner’s manual specifically states why:

DRY-FIRING: Going through the actions of cocking, aiming, and pulling the trigger of an unloaded gun is known as “Dry Firing.” It can be useful to learn the “feel” of your revolver….The Ruger Old Army can be dry-fired without damage to the firing components.

Another unusual feature of the Old Army is that—unlike the old-time guns and their modern replicas—it isn’t a .44 caliber, but a .45. Original guns and replicas normally use a 0.451” round ball, The Old Army Manual states that:

The “Old Army” is designed to use a .457” diameter round ball or .454” conical bullet of pure lead. Bullets of either type can be purchased from your dealer, ready to use, or can easily be cast at home with a small investment in equipment.

When loading a percussion revolver cylinder a slightly oversized bullet is normally used: thus a thin lead ring is shaved off as the ball/bullet is rammed home, ensuring a tight fit, a good gas seal, and minimal chances of a “flash over” or “chain fire.” The 0.457” ball is required to properly seal the chamber of an Old Army, while a conventional 0.451” ball will simply drop to the bottom. But why use the 0.457” bullet? Why not use the more common size?

While the groove diameter of a nominally “.44” caliber cap and ball gun is 0.450”, the groove diameter of the Old Army’s barrel is larger: 0.452”. This is the diameter Ruger uses in centerfire handguns chambered for the .45 ACP. I have no authoritative information as to why the larger diameter was chosen but it may have been done to allow use of the same rifling machinery for Old Army barrels as centerfire ones, thus lowering production costs. The larger groove diameter has implications for the versatility of the gun, too, as will be seen below.

The Old Army was an instant hit with shooters who wanted a big-bore percussion revolver, but weren’t especially interested in historical authenticity. It was made in both blued steel and stainless steel: those who shoot black powder guns like stainless steel’s resistance to corrosion. Another feature that sets it apart from the BP guns of yesteryear and most of the modern replicas is the Old Army’s fully adjustable sights. They are very good ones, too: a squared off, deep rear notch and a matching “Patridge” style square blade front sight on a ramp. Combined with the long sight radius of a 7-1/2” barrel, they gave the Old Army a level of inherent accuracy none of the old guns and few of the replicas could match.

The Old Army’s strength, durability, and accuracy attracted attention from the CAS shooters, but adjustable sights are not permitted in CAS main matches. So in 1994 Ruger addressed the needs of CAS competition by making Old Armies with a fixed sighting groove and a rounded, non-ramped front sight. Fixed-sight guns with 5-1/2” barrels were produced after 2002. But these variants represented a small portion of the total produced, and by far the most common configuration found today is a stainless steel gun with a 7-1/2” barrel and adjustable sights.

Thanks to its combination of sound design, modern materials and production methods, and its very strong frame, the Old Army simply couldn’t have been produced in The Good Old Days, anywhere, by anyone. If for some reason fixed ammunition had never been invented, Bill Ruger’s percussion-fired Old Army would undoubtedly be regarded as the absolute zenith of handgun technology, a product Sam Colt, Horace Smith, and Daniel B. Wesson would regard with envy.

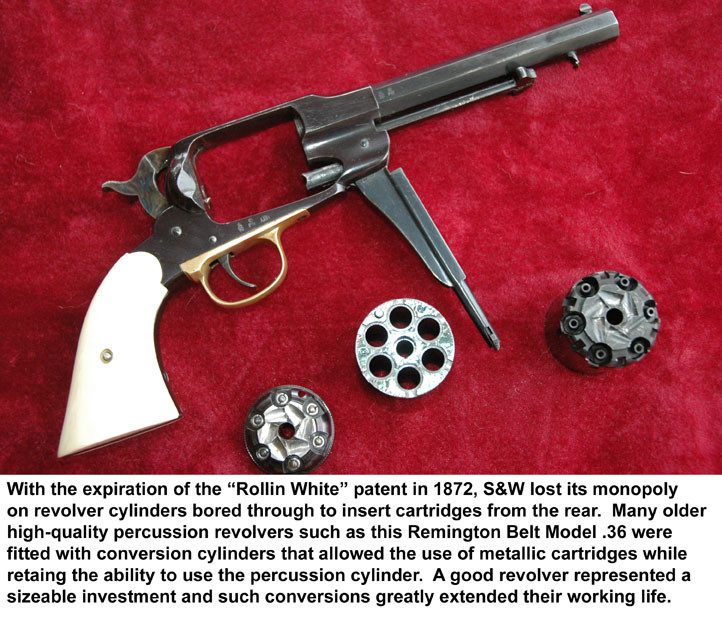

Percussion ignition was really a “transitional” technology with a fairly short life in the open market. Beginning in the mid-1850’s Smith and Wesson started making revolvers using fixed ammunition fired from cylinders bored completely through from the rear: they held the rights to this so-called “Rollin White Patent” until 1872, when it expired. At that point, when any maker could use the method, the very significant advantages of fixed ammunition more or less swept the old percussion technology away in a few years. However, many thousands of high-quality percussion handguns (each representing a significant investment on the part of its owner) remained in existence. Cleverly-designed conversion cylinders that allowed them to use self-contained were eventually made in various forms.

The most common type for the Model 1858 Remington consisted of a cylinder with a removable back plate. Dropping the cylinder allowed cartridges to be inserted into the chambers; the back plate was replaced and the cylinder put back into the frame. This was much faster than the usual loading procedure for a cap-and-ball gun; moreover it provided far more reliable ignition. And here, again (though it probably wasn’t something Ruger envisioned in the early 1970’s) the Old Army held an advantage over traditional replicas.

A “cottage industry” producing new-made conversion cylinders for various replica revolvers has evolved in recent years, and such replacement cylinders are readily available on the open market, through catalogs or direct from the manufacturers. Thanks to the universal use of CNC machining in gun production nearly all of these are “drop in” for whatever style of gun they’re intended to fit. Though not cheap, they allow a shooter to use fixed ammunition of “Cowboy Action” power levels in replicas. Those for the .44 percussion guns usually shoot .45 Long Colt. (Others using .38 Long Colt, .38 Special or even .32 S&W are available for smaller caliber replicas.) Despite the differences in caliber nomenclature, for reasons too complicated to discuss here, it’s quite safe to use a .45 Long Colt cartridge in a steel framed replica nominally of “.44” caliber.

A “cottage industry” producing new-made conversion cylinders for various replica revolvers has evolved in recent years, and such replacement cylinders are readily available on the open market, through catalogs or direct from the manufacturers. Thanks to the universal use of CNC machining in gun production nearly all of these are “drop in” for whatever style of gun they’re intended to fit. Though not cheap, they allow a shooter to use fixed ammunition of “Cowboy Action” power levels in replicas. Those for the .44 percussion guns usually shoot .45 Long Colt. (Others using .38 Long Colt, .38 Special or even .32 S&W are available for smaller caliber replicas.) Despite the differences in caliber nomenclature, for reasons too complicated to discuss here, it’s quite safe to use a .45 Long Colt cartridge in a steel framed replica nominally of “.44” caliber.

Needless to say, such conversion cylinders are made for the Old Army. But thanks to the Old Army’s unconventional 0.452” groove diameter, it’s also possible to make a conversion cylinder for the .45 ACP, as well as one for the .45 Long Colt. No traditional replica revolver has this capability.

Having a couple of these cylinders vastly enhances the utility and practicality of the Old Army. The .45 Long Colt, which is very popular in CAS shooting, is a potent round, even in factory-level loadings. It’s not up to .44 Magnum levels but it’s nothing to be sneezed at. The .45 Long Colt has been in continuous production since 1873 and it’s as good a round for self-defense and hunting as it ever was. The US Army used it as a standard-issue handgun cartridge between 1873 and 1892. (Its replacement, the .38 Long Colt, performed so poorly in the Philippine Insurrection of 1901-03 that older revolvers chambered for .45 Long Colt had to be removed from storage and re-issued!)

The .45 Long Colt’s drawback for the average shooter is cost: factory ammunition, as of this writing, is about $43 per box of 50 rounds. The .45 ACP is another story: its wide popularity means many companies make it and offer at about half the price of .45 Long Colt, or even less. Both can be reloaded at considerable savings to the shooter with a minimal investment in equipment.

With an overall length of 13-1/2” and a weight of nearly 3 pounds the Old Army is a very big gun, hardly suited to concealed carry. But it’s quite powerful enough for any situation or hunting scenario not calling for a .44 Magnum.

Just how powerful is it? Using the percussion cylinder, I shot a 240-grain conical bullet over 30 grains of GOEX FFFg black powder. This produced 858 FPS and 395 F-P of muzzle energy: more or less identical to the performance of Remington’s factory load for the .45 Long Colt. I used that Remington factory load in the conversion cylinder. It fires a 250 grain bullet at a nominal velocity of 860 FPS, for 410 F-P of muzzle energy. That’s identical to the performance of the original black powder loading in this caliber, as well as that of the percussion cylinder.

Remington’s factory load in the Old Army developed 858 FPS and 408 F-P, spot on what the factory said it should be. A “Cowboy Action” handload using a 225-grain bullet over 8.5 grains of Alliant Unique outperformed the factory stuff by a slight margin: 1009 FPS and 509 F-P of energy. The conclusion has to be that the Old Army is at least the equal of any of the more famous guns of the Civil War and the Wild West. Add to that its corrosion resistance, inherent accuracy, and rugged internal mechanism and I think any cowboy or frontiersman would have been happy to carry an Old Army on his hip.

Both the .45 Long Colt and .45 ACP cylinders give the Old Army an additional utility: as a sort of mini-shotgun. Commercially-manufactured shotshells are available in these two calibers, and they provide a devastating defense against dangerous snakes. When tromping around snake country, an Old Army with shotshells would be a comforting companion.

A gun this big requires a holster, preferably one with a flap that protects the gun in case of a fall. If the percussion cylinder is in place the flap will protect it against weather. On horseback, a saddle holster is probably preferable to one on the waist. (I’m no horseman, but if I were, I’d have my gunsmith add a lanyard loop, a simple procedure.)

A gun this big requires a holster, preferably one with a flap that protects the gun in case of a fall. If the percussion cylinder is in place the flap will protect it against weather. On horseback, a saddle holster is probably preferable to one on the waist. (I’m no horseman, but if I were, I’d have my gunsmith add a lanyard loop, a simple procedure.)

Carrying a six-shot single action safely requires a bit of thought, even when it’s holstered. The percussion cylinder has safety notches between the chambers: the hammer can be lowered (very carefully) into one of them, where it will rest solidly against the steel, and prevent the cylinder from rotating to put a cap under the hammer nose. The last thing you want to have happen is to drop the gun and have it land on the hammer when it’s positioned over a live chamber! The cartridge-firing cylinders don’t have the notches, but they do have enough space between chambers that the hammer can safely rest there. A routine safety recommendation is to load only 5 chambers and leave the hammer down on the empty sixth one. (It is often said that this was standard practice in The Wild West, but I have my doubts as to the accuracy of that statement. Since no one today is in danger of losing his hair to marauding Indians or of being held up by stagecoach bandits, however, it’s probably not a bad idea in view of the lack of safety notches.)

Can you use the Old Army for hunting? Assuming it’s legal, yes. It would certainly kill small game cleanly, and with the shotshells could even serve for animals such as squirrels and rabbits. It would be amply powerful for medium sized animals such as coyotes or cougars, without doubt; and even for deer, given proper bullet placement and design. A flat-nosed semi-wadcutter clipping along at 900 FPS or so would do the job on a whitetail, if he were hit in the right spot. I’d not depend on any .45 caliber revolver for defense against a large and angry bear, but it would be better than a knife or bare hands (ha, ha). I’d certainly not select it as a primary hunting gun for big game: but there are worse choices and as a “backup” it would be an excellent option. I’d have no hesitation using it on a feral hog, either as a percussion of centerfire gun.

Alas, Ruger discontinued this fine gun in 2008, and prices in the used gun market are steadily rising. It’s very difficult to find any Old Army for much under $600 and many go for more. The comparatively scarce 5-1/2” barreled guns and the ones with fixed sights are so much in demand for Cowboy Action shooting that their prices have risen even faster than the more common stainless steel 7-1/2” barreled guns: I have seen them on offer for nearly $800, if they can be found at all.

I’m at a loss to explain why Ruger isn’t making the Old Army any more, given its popularity and utility, but I’d hazard a guess that the conversion cylinders have something to do with it. These started showing up on the market about 10-15 years ago, just about when Ruger called a halt to production. Perhaps their corporate lawyers were concerned because even though the cylinders are rated for smokeless powder ammunition using Cowboy Action loads, there is always the possibility that some yahoo will brew up reloads too hot for the gun, and someone will get hurt. That Ruger had no hand in the manufacture of after-market conversion parts would not prevent some Whiplash Willie from suing them claiming they “knew or should have known” about the conversions’ alleged danger. Reading through the Owner’s Manual for the Old Army, nearly half its pages are taken up by dire warning about bad things that might happen if you misuse it, and/or are terminally stupid. Such things are par for the course in today’s litigious environment, unfortunately.

Another reason may be that the Old Army is not subject to Federal law. Since it uses loose powder and ball, it is legally classed as an “antique” by statute, despite its modern design and manufacture. It’s completely exempt from all provisions of the Gun Control Act of 1968. An Old Army can be sold to anyone, even across a state line, without the intervention of a dealer, so far as federal law is concerned (some states differ). The separate conversion cylinders are considered “unregulated parts” by the BATF, and anyone can buy one. Putting the two together does indeed mean you have “manufactured” a “ firearm” as the GCA68 defines it, but that’s also legal if it’s for your own use and not for resale. It’s conceivable that Ruger’s lawyers and accountants worried about this happening, and the chance that the converted gun might be used for an illegal act. As ridiculous as this scenario sounds to a rational person, and as preposterous as it might seem to hold Ruger accountable for misuse of a product they didn’t make, I believe this fear may have been a factor in the decision to terminate production of one of the most innovative, versatile, and just-plain-fun handguns ever made. A pity.

| HUNTING | GUNS | DOGS |

| FISHING & BOATING | TRIP REPORTS | MISCELLANEOUS ESSAYS |

| CONTRIBUTIONS FROM OTHER WRITERS|

| RECIPES |POLITICS |